Andrew Brown (@andrewbrown365) and Sam Thomas (@iamsamthomas)

The annual report from the HM Inspectorate for Prisons (HMI) was published this week, and it makes for challenging reading.

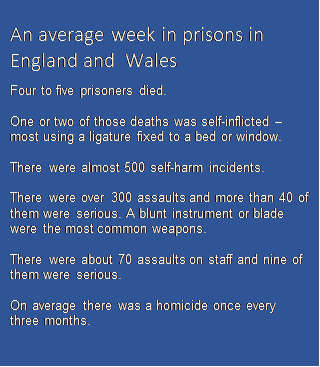

The report highlights shortcomings turned up by inspections over the last year, notably the lack of rehabilitation for prisoners, and the issues of staffing and overcrowding that have had a ‘significant impact’ on prisoners’ safety. The severity of this impact is clearly illustrated by the stark figures presented to the right.

The report highlights shortcomings turned up by inspections over the last year, notably the lack of rehabilitation for prisoners, and the issues of staffing and overcrowding that have had a ‘significant impact’ on prisoners’ safety. The severity of this impact is clearly illustrated by the stark figures presented to the right.

HM Chief Inspector of Prisons Nick Hardwick uses what will be his last report in the role to raise three key challenges he has seen over his five year tenure in the post:

First, the increased vulnerability of those held across the range of establishments we inspect and the challenge establishments have in meeting these individuals’ needs. Too often locking someone up out of sight provides a short-term solution, but fails to provide the long-term answers more effective multi-agency community solutions would provide.

Second, there is a real need to match the demand for custodial services to the resources available. Detention is one of the public services where demand can be managed. Alternatives to the use of custody may be unpalatable but so, no doubt, are the other public expenditure choices that government has to make.

Third, the case for the independent inspection of custody remains as strong as ever and that independence needs to be preserved.

The detail of the report, particularly the annual questionnaire that is done with prisoners, throws up some interesting figures on drug misuse and mental health problems, which builds on and confirms what we already know about the scale of the challenge.

Mental health

The report raises concerns over the mental health care that prisoners are receiving, noting:

Many prisons had gaps in primary mental health care, in particular, an absence of counselling services, and many continued to have problems in transferring patients to mental health units within the current Department of Health guideline of 14 days.

Given the high levels of mental health problems within the prison population, this is cause for serious concern. The survey carried out by the Inspectorate indicates that one in five (19%) of male prisoners said they had a mental health problem when they arrived in prison, this rises to a third (35%) saying they have a current problem.

The position seems to be worse for women prisoners where over half (58%) of women prisoners said they had concerns about their mental health or wellbeing. The inspection for one women’s prison, Low Newton, commented that:

“…however good the level of care offered, the question remains about why some of these obviously very ill and troubled women are in prison at all, rather than in a health setting which would be much more appropriate for their needs.”

Drug and alcohol misuse

The report has some positive things to say about the quality of drug and alcohol treatment in prison, though suggests that this is being hampered by the lack of prison officers to escort prisoners to and from their cells; meaning that too many prisoners aren’t able to access group work or peer support.

In the survey, 41% of women and 28% of men said they had a problem with drugs before they came to prison. 30% of female prisoners said they had a problem with alcohol before entering prison, but only 19% of men said they did. This is somewhat lower than the levels indicated by a 2008 UK Drug Policy Commission paper on the links between drug use and offending, which suggests that between a third and a half of new receptions to prison are estimated to have significant drug problems.

The report doesn’t discuss issues around co-existing substance misuse and mental health problems (sometimes referred to as ‘dual diagnosis’), which may be a missed opportunity to recognise the needs that many prisoners have in this area. A recent paper from the Rehabilitation for Addicted Prisoners Trust (RAPt) on substance use and mental health in prisoners suggested that their service users present with an average of 3.4 mental health problems each.

New psychoactive substances and the supply of drugs in prison

As with last year’s report, the HMI reflects on quite widely held concern about the extent to which Novel Psychoactive Substances (NPS) have penetrated prisons (particularly men’s prisons) and the correlation that is drawn between their use, increased violence and hospitalisation of prisoners. The report also suggests that the use of NPS means figures about drug use in prison derived from drug testing are an unreliable source of data for policy makers.

The HMI is less than sanguine about efforts to control the supply of illicit substances, and judges that “too many prisons had an inadequate strategy to reduce the supply”.

The HMI is less than sanguine about efforts to control the supply of illicit substances, and judges that “too many prisons had an inadequate strategy to reduce the supply”.

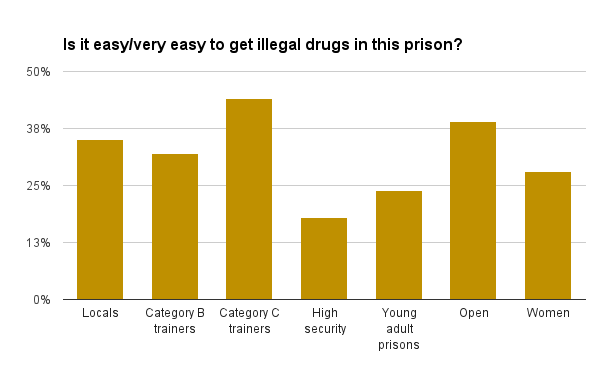

In the survey, significant minorities of prisoners from across the prison estate say that accessing drugs in their prisons is easy or very easy. This is worrying in a context where 8% of male adult prisoners said they had developed a problem with drugs since coming to prison, with a further 8% saying they had developed problems with diverted medicines.

Housing needs

As well as exploring needs within the prison population, there’s also a question in the survey on housing needs people had before coming to prison. This indicates that 15% of male adult prisoners had a problem with accommodation prior to entrance, and encouragingly the commentary suggests that all prisons were doing something to support those likely to leave custody without appropriate accommodation.

However, it is also slightly critical of the unevenness of follow-up support after release. Given what we know about poor resettlement outcomes for prisoners, it’s to be hoped that the coming changes under Transforming Rehabilitation will help to address this.

In conclusion

It’s encouraging to see the report acknowledge the very real challenges around prisoner safety, and how substance misuse problems and inadequate mental health care in the estate contribute to these.

This evidence reinforces a well-established and unacceptable picture of what life is like inside our prisons – although on some issues, such as substance misuse, that picture is still not as clear as we would like. Policymakers should frame their response to Nick Hardwick’s report with the urgency its findings demand.

Thanks to our colleague Nicola Drinkwater at MEAM coalition partner Clinks for her help in writing this blog.